Navigating Rates

What could higher tariffs mean for trade finance?

Higher tariffs planned by Donald Trump against China, Mexico and other big trading partners could shake up global trade patterns. But we think trade finance can adapt to a more protectionist global landscape as businesses continue to need financing for domestic and cross-border deals.

Key takeaways

- The investable universe for trade finance is expected to grow, even with the dampening effects of protectionist policies as global commerce continues.

- History shows that trade finance can withstand the impact of tariffs: evidence from Mr Trump’s first term in office suggests tariffs did not hinder growing finance volumes.

- We think a diversified investment strategy without relying too heavily on any single market, transaction type, or sourcing channel can help investors seeking stable, uncorrelated returns.

In his return to the Oval Office, Donald Trump has signalled his intention to reignite the US-China trade war he instigated during his first administration. This time, however, his "America First" trade policy is expected to be even more protectionist than before, intensifying measures already in place. His proposals include a 10% universal import tariff, and tariff rates ranging from 25-60% for the country’s three largest trade partners, China, Mexico, and Canada.

Of course, the policies that emerge may be less severe. Mr Trump’s nomination of Scott Bessent as US Treasury secretary is viewed by financial markets as a sensible choice and may signal that trade policies can be moderated. Even so, investors need to be prepared for a choppier trade environment.

What impact could higher tariffs have on trade finance?

Despite the undoubted dampening activity of higher tariffs, we think trade finance demand will persist and adapt to the changing patterns of commerce in a more volatile and protectionist global trade landscape.

Consider how the market responded to tariffs introduced under Mr Trump’s first term in office. From 2016 to 2020, the Trump administration focused on economic nationalism, aiming to reduce the trade deficit, especially with China, by implementing tariffs and renegotiating trade agreements. By 2018, tariffs on Chinese imports reached USD 360 billion, with rates up to 25%. Other industries, such as steel and aluminium, also saw increased tariffs as part of this protectionist approach.

What happened to trade after previous tariff rises?

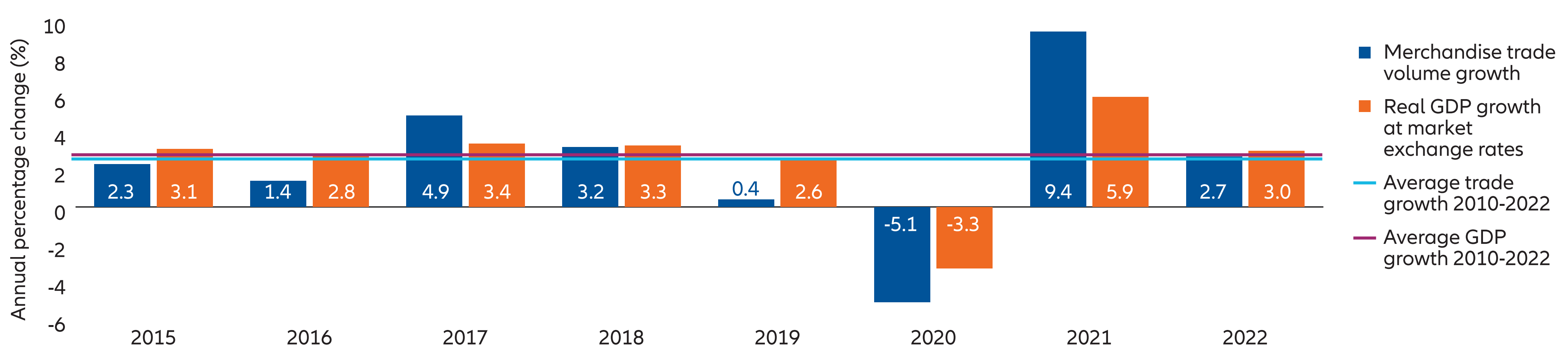

The growth in world merchandise trade volume decelerated meaningfully in 2019,1 shortly after the introduction of US tariffs, and during a year of weaker global growth. Trade volumes in the 2019-2022 period grew, but at a slower annual pace than the 2015-2018 period (see Exhibit 1). However, a closer examination of broader data suggests Mr Trump’s tariffs may have disrupted global trade only marginally.

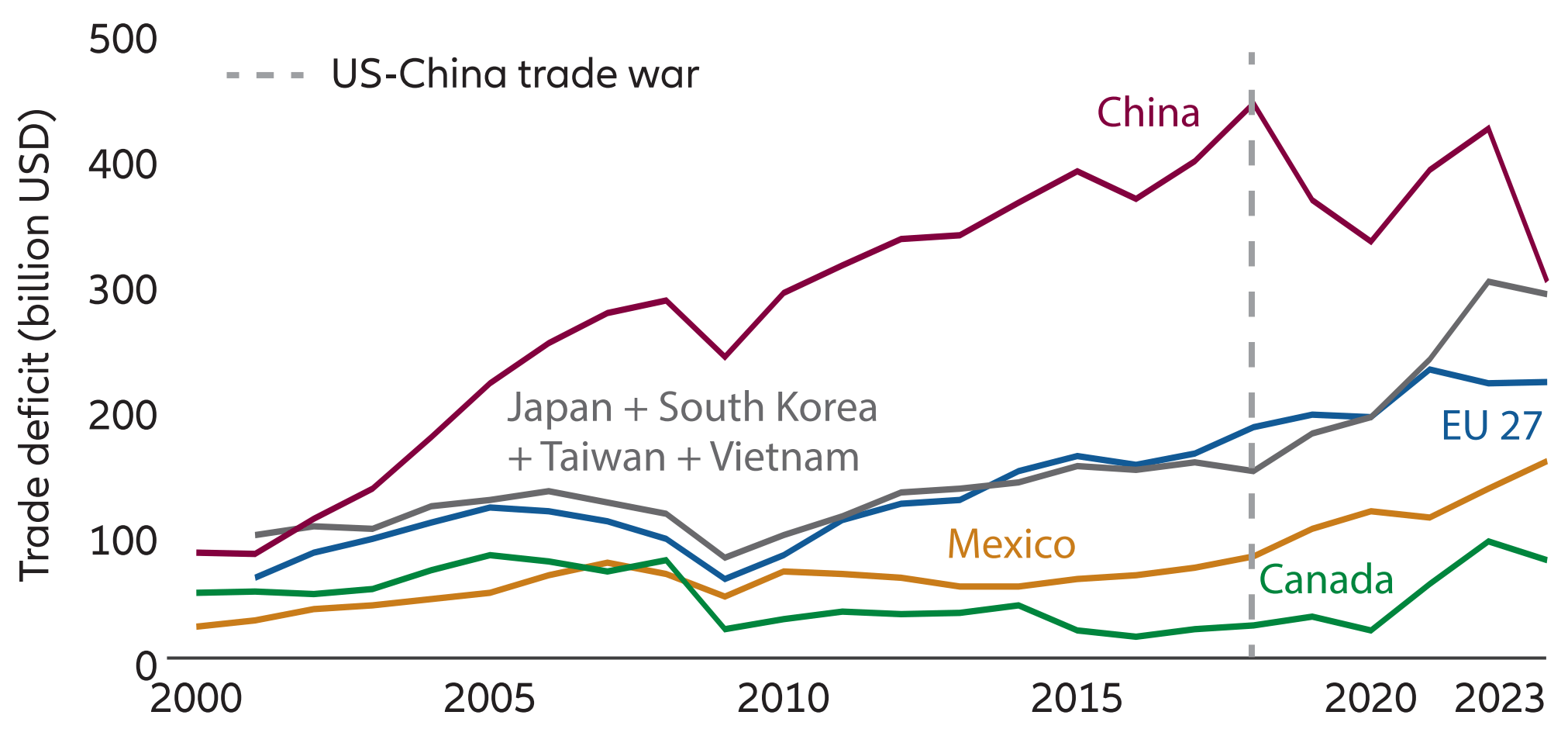

- Between 2019 and 2022 the US’s trade deficit with China almost halved, from 46% to 27%.2 But this was more than offset by the growing trade deficit the US had with Southeast Asia, North American neighbours and other countries.

- The growth in the US’s overall trade deficit – from 2.8% of GDP in 2016 to 3.7% of GDP in 2022 (see Exhibit 2) – reflected the US importing a greater share of goods from countries outside of China.

- But the US’s shift in trade likely accelerated an existing trend of a gradual erosion of China's competitiveness in lower-value manufactured goods due to its economic growth and rising labour costs.

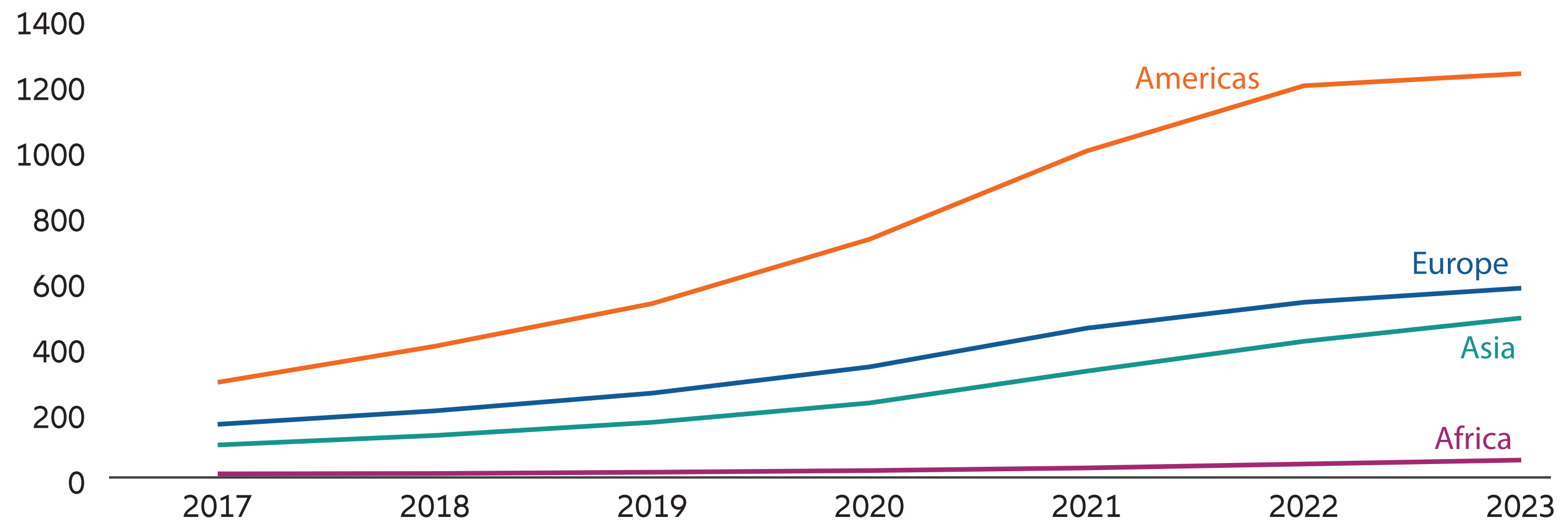

- Globally, and adjusting for the disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, the magnitude of the hit to trade as a share of GDP was rather limited.3 In fact, by 2022, international trade as a share of global GDP exceeded 60% for the first time in a decade (see Exhibit 3), despite the higher level of tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade, and the slowing growth of trade superpower China.

Exhibit 1: Trade volumes in the 2019-2022 period grew at a slower pace than the previous three years

Source: WTO for merchandise trade volume, consensus estimates for GDP.

Exhibit 2: The US’s trade deficits with major trading partners have shifted

Source: Comtrade, www.econovis.net

Exhibit 3: Global trade as a share of GDP reached its highest level in a decade in 2022

Source: Compiled by World Bank (2024) – processed by Our World in Data

And evidence from the trade finance market suggests tariffs have not hindered growing finance volumes (see Exhibit 4).

The total volume of supply chain finance – the trade finance most prevalent with global large corporates – has grown by a compound annual growth rate of 26% from 2017 to 2023 despite potential headwinds from trade protectionism, according to an industry survey conducted by BCR Publishing.4

Exhibit 4: Trade finance volumes have continued to grow

Volume (USD billion)

Source: BCR Publishing

Growth has been more muted in other segments of trade finance. Factoring, used by small businesses and mid-market companies to raise finance against their invoices payable by high quality buyers, has seen a compound annual growth rate of about 5% over the 2017 to 2023 period, according to Factors Chain International (FCI),5 which monitors the total volume of factoring. But the rate of growth still exceeds G10 annual GDP or world trade growth, indicating factoring is still integral to financing commercial trade.

What next under Trump 2.0?

The World Trade Organisation (WTO) expects global trade to accelerate to 3% in 2025, up from 2.7% in 2024.6 The forecast, made before the election of Mr Trump, points to a gradual recovery in trade despite policy uncertainty and regional conflicts.

But the unknown for 2025 is whether Mr Trump pushes ahead with trade protectionist measures that could be more extensive than in his first term. Our colleagues at Allianz Trade estimate that as much as USD 510 billion in global exports could be at risk, potentially reducing annual global GDP growth by nearly one-third.7

A range of secondary effects and feedback loops are likely to emerge, creating distinct winners and losers. These evolving terms of trade will have widespread effects on countries, industries, and individual companies that depend on international trade.

But if history is any guide, we can expect global commerce to withstand any onset of more protectionist measures, fuelling continued demand for trade finance.

What explains the resilience of trade finance?

Trade finance has shown remarkable durability in the face of trade wars and other geopolitical shocks. In fact, despite the slowing growth trend in global trade, the so-called trade finance gap, which measures the difference between demand for trade financing and its supply, has been increasing in past years. As of the latest data in 2022, it is USD 2.5 trillion – up from USD 1.5 trillion a few years ago.8 A few things help to explain this:

- Trade finance is not just focused on international deals: Trade finance supports both domestic and cross-border transactions. As supply chains shift due to protectionist measures, trade finance remains essential, enabling companies to manage increased import costs, enter new markets, and establish relationships with new buyers and suppliers.

- Demand for trade finance from corporate treasurers is rising: Over the years, corporate treasurers have increasingly relied on trade finance to meet recurring working capital needs. These financing programmes provide short-term liquidity, making them a dependable tool that scales with a company’s growth. As trade relationships evolve, these programmes adapt with them and help to ensure continuity of working capital liquidity in the supply chain.

- Trade finance can help to mitigate risk in uncertain times: Trade finance also helps companies manage risk, offering a way to reduce financial uncertainty during geopolitical and economic change. This risk mitigation capability makes trade finance especially valuable as companies adjust to shifting supply chains.

What does a more protectionist world mean for trade finance investors?

As geopolitical risk becomes a bigger consideration for investors, trade finance can provide a safe haven, offering insulation from external shocks. The asset class's lack of correlation with financial markets shields it from major selloffs, making it particularly resilient during prolonged periods of geopolitical uncertainty.

The investable universe for trade finance is expected to grow, even with the dampening effects of protectionist policies. The launch of Basel IV in 2025 across major markets like the EU, UK and US requires banks to hold more capital against trade finance assets. As banks become more reliant on external investors to meet these requirements, new opportunities will open for trade finance investment managers.

We think a diversified investment strategy without relying too heavily on any single market, transaction type, or sourcing channel can help investors seeking stable, uncorrelated returns. This approach balances risk and return, providing stable access to opportunities across the asset class.

Caution is warranted around trade finance strategies centred around China-US export flows. Rising tariffs and protectionist policies could make these trade routes unsustainable and elevate the risk of defaults.

Despite potential headwinds from renewed protectionist policies, trade finance has shown resilience as an asset class and continues to offer promising opportunities for investors seeking stable, uncorrelated returns. By adopting a defensive and diversified strategy, investors are best placed to capitalise on the inherent stability and resilience of trade finance, making it a potentially valuable addition to fixed income portfolios, especially in uncertain times.

1 Source: World Trade Statistical Review 2023

2 Source: US Trade Deficit Shifts: Decreases with China, Increases with Other Major Partners, Voronoi

3 Source: Trade as a share of GDP, 1960 to 2022, Our World in Data

4Source: World Supply Chain Finance Report, 2024, BCR Publishing

5 Source: International Factoring - Statistics, FCI

6 Source: Gradual trade recovery underway despite regional conflicts, policy uncertainty, World Trade Organisation, 11 October 2024

7 Source: What to watch: The return of Donald Trump and the implications of a Republican sweep, Allianz Research, 7 November 2024

8 Source: Global Trade Finance Gap Expands to $2.5 Trillion in 2022, Asian Development Bank, September 2023