Embracing Disruption

Geographies of tech – rivalry, fragmentation, and deglobalisation?

While the Covid-19 pandemic threw a spotlight on the potential vulnerability of global supply chains, many corporates were already evaluating their dependency on certain countries and regions even before this unprecedented shock to the global economy. Indeed, growing trade tensions between the US and China, the pandemic, and the war in Ukraine have led to significant changes in patterns of trade, a trend that is likely to continue as geopolitical uncertainty – one of several key drivers here – seems unlikely to abate any time soon. As such, we are hearing more and more about nearshoring, reshoring, and “China plus one”.

A further key driver, and one that is inextricably tied up with geopolitical issues, has been the growing rivalry between the US and China in the tech sector. While this is most notably being played out in the conflicts around semiconductor production, we are also seeing intense competition in software development – leveraging recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI), for instance – and around leadership in global standards setting. Indeed, given that tech companies are among those potentially most exposed to sudden and unexpected supply disruptions, the stage is set for a radical realignment in this sector as corporates seek to protect themselves from overreliance on shocks and governments vie to advance their national interests. We believe this will lead to the growth of rival “tech hemispheres”, where a battle will emerge among the largest powers to pull emerging members of the Global South into their respective orbits.

While the impact of these changes will most notably be felt in the US and China, the effects will of course have implications for the global economy. Semiconductor development and manufacturing is vital for some of the most exciting and fast-growing markets – AI and electric vehicles (EVs), for example – while also being key to supporting national security interests.

Meanwhile, Taiwan’s technology industry, particularly its semiconductor industry, has become a key focus in the growing US-China rivalry. One of the largest Taiwanese semiconductor companies dominates the dominates the production of many sorts of chips vital to both civilian and other uses; as a result, Taiwan finds itself at the center of an increasingly tense rivalry.

These changing geographies of tech will be keenly observed by investors and other market participants.

The US, the incumbent

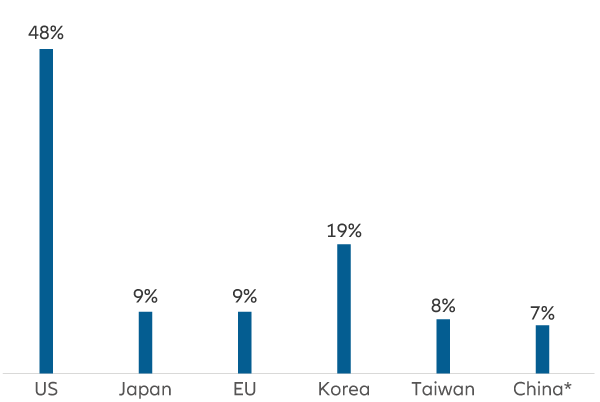

As the two charts below show, the US sits in the invidious position of having the world’s greatest demand for semiconductors, while currently possessing limited manufacturing capacity compared to its competitors and peers.

Exhibit 1: Semiconductor demand

* 2022 data for the Chinese market is incomplete, so market share

percentage is based on 2021.

Source: AllianzGI, Nov 2023

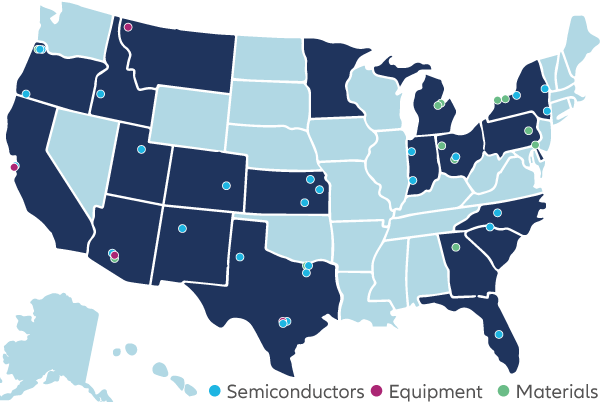

Exhibit 2: Wafer Manufacturing Capacity, by Fab Location and Chip Type, 2020

Source: CRS, adapted from SEMI, World Fab Forecast, November 2020.

A watershed moment in the current realignment was the passing of the CHIPS and Science Act in 2022, designed to boost US development and manufacturing of semiconductors through subsidies, tax credits, and research funding. Indeed, the periods prior to and after the passing of this legislation saw the announcement of many significant investments in this sector across the US.

Exhibit 3: The Chips Act in Action

Source: AllianzGI, Nov 2023

Around this time, the US Department of Commerce also introduced export controls on advanced AI chips, and these were recently tightened to eliminate workarounds.

Despite this positioning and strong rhetoric, the US remains in a catch-22 situation; key US corporates derive over 20% of their revenues from China and the Chinese market remains an important growth driver for many US companies in this sector. Indeed, restricting sales into China will accelerate the replacement of US components in Chinese products, damaging some US players and aiding China’s own strategic interests. In addition, the US Federal Government’s perceived bias against “big tech – there are currently anti-competitive cases against several of the “Magnificent Seven” ongoing – is also seen as unhelpful by many.

Outside of semiconductors and hardware, the battle for tech dominance can also be felt across several other areas. Chinese tech companies are appealing to western consumers, while Chinese EV companies are aggressively seeking market share in Europe and the US. Indeed, while semiconductors are the key driver for the current realignment, the rivalry will play out across the tech sector and beyond.

Despite growing competition from China and elsewhere, the US remains a leader in many key sectors; its dominance here should not be underestimated and it will not be displaced for some time.

China, the challenger

Calls for self-sufficiency in China are nothing new, yet have often been seen as an empty slogan – expecting Chinese companies to favour domestic components when they had little incentive to do so, financial or otherwise, was never realistic when they are facing the same competitive pressures as their foreign peers. Yet due to national considerations, including moves from the US to restrict access to its own production, the landscape has changed and we are now seeing serious efforts to move in the direction of self-sufficiency in several areas.

These changes are providing opportunities for Chinese component makers to penetrate the mid to high end domestic market, and develop their products and experience while doing so. One great example of this type of rapid innovation comes from a well-known domestic technology giant; the company recently launched a 5G smartphone with a high localization rate – it even features a 5G mobile processor which is supposedly not possible to be manufactured under the latest US technology restrictions.

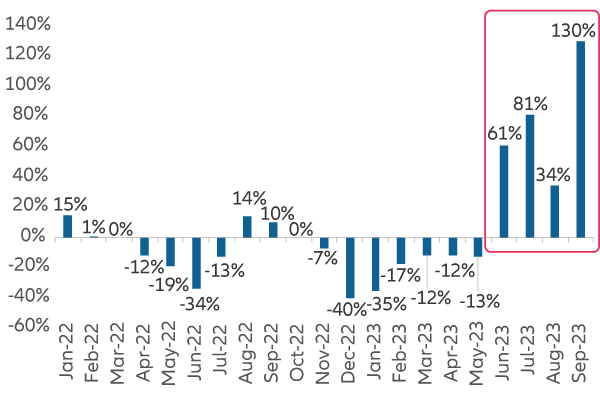

Indeed, while there is an acceptance that China still lags some of its overseas peers, we have recently seen notable improvements in the competitiveness of domestically produced semiconductor equipment, with some manufacturers even gaining traction with overseas customers. Indeed, recent customs data suggests that China has been accelerating the import of wafer fabrication equipment imports in recent months.

Exhibit 4: Balance of trade in semiconductor production equipment

Source: UBS, May 2023

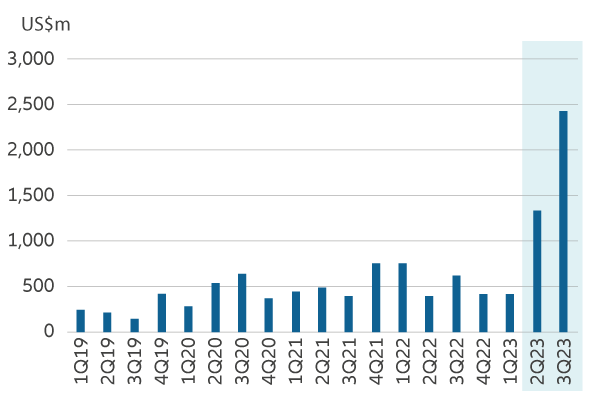

Exhibit 5: Chinese wafer fabrication imports

Source: UBS, May 2023

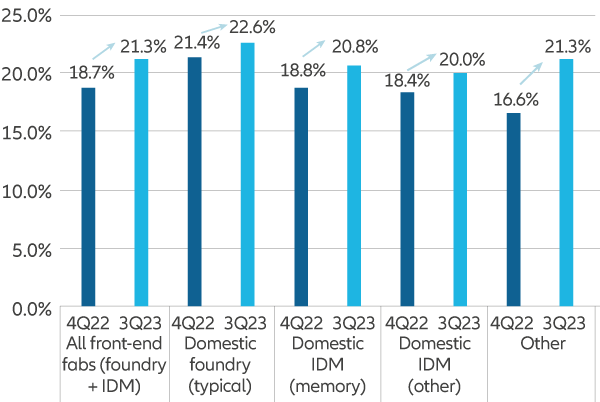

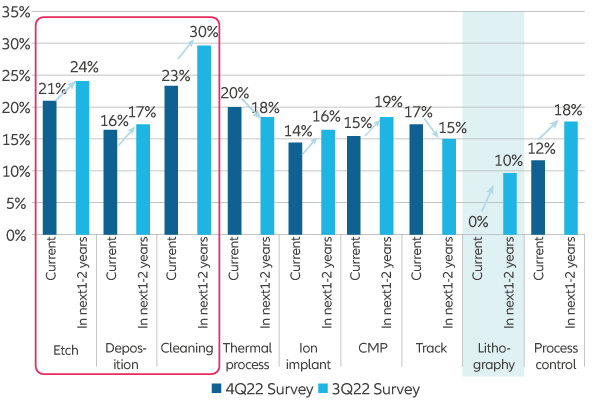

And it is also no secret that China is running on full steam to develop their own deep ultraviolet (DUV) equipment (it currently relies on imports from the Netherlands). More evidence of localization comes from a recent UBS survey of 75 respondents within the Chinese semiconductor industry. The results showed an increase in average localization rate in existing (and expanding) production lines.

Exhibit 6: Semiconductor production localisation rates

Source: UBS, May 2023

Exhibit 7: Semiconductor production localisation rates

Source: UBS, May 2023

Respondents also mostly anticipated the localization rate of wafer fab equipment in China to continue increasing over the next one to two years. Indeed, we believe this expansion in domestic manufacturing capacity may continue for up to the next five to 10 years.

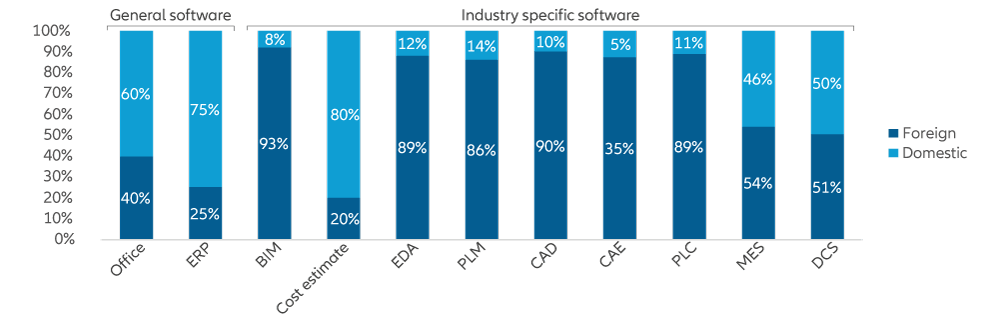

Software is another area where China is spending much effort in localization. This is further aided by Xinchuang, the term referring to government localization, aiming to achieve self-control overall system security and promote technically competitive domestic IT companies. Localisation has been happening for some time and we now find that the market penetration of general software such as office applications, ERP1 , and less complicated industry specific software like MES2 and DCS3 , have achieved a relatively high localisation rate. And more efforts will be placed to close the technology gap for more complicated industry specific software.

Exhibit 8: Market share of selected software sectors

Source: Gartner; Huanon; CCID; Bernstein estimates and analysis

Cost estimate domestic market share is estimated using Glodon as reference

The rest of the world; quo vadis?

While Europe contains some attractive prospects buoyed by the EU’s passing of its own “Chip Act”, the key technology hub outside of the US and China, especially with respect to semiconductor production, is Taiwan. In addition to the vital importance of Taiwanese chips, US manufacturers have begun moving some parts of their supply chains out of China and into Taiwan and other Southeast Asian locations such as Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, and India.

Driven by technological developments and geopolitical changes, the global economy is clearly entering a period of realignment, and we believe that tech and related sectors are likely to be the most impacted by changing supply chains. With two principal tech leaders and many emerging economies, there will inevitably be fierce competition to do business with these future powerhouses of the Global South. As the world will increasingly start looking in two directions for its tech leaders, investors should do the same; both quality and growth will be found across both continents for the foreseeable future and portfolio composition should continue to reflect this.