Interpreting China

Growing pains? China’s property sector challenges signal an economy in transition

China’s property sector is a significant engine of the country’s economy, and uncertainty around the outlook is weighing heavily on market sentiment. But we view these challenges as growing pains in the shift of China’s economy to a more consumption-led model. What are the opportunities of this transition?

- High debts, empty housing units and weak consumer sentiment are casting a shadow over the property sector – a key driver of China’s economy.

- We believe the risk of a broader systemic crisis is contained and that policymakers will eventually roll out significant fiscal stimulus to support the property sector and wider economy.

- For the global economy, China’s challenges may help dampen inflationary pressures, but also lower global growth prospects.

- In our view, investment opportunities in China remain in play – from artificial intelligence (AI) to big data; local government bonds could respond positively in the event of strong policy support.

The difficulties faced by China’s property sector – a major growth engine of the world’s second-largest economy – have understandably unsettled financial markets. A multi-year property boom has faded as some developers struggle with huge debts and empty housing units. A dip in consumer confidence is also weighing on the sector. Chinese consumers have long viewed housing as a store of wealth, but confidence remains low, even after the lifting of Covid-19 restrictions.

It is a critical moment for China. The global economy is slowing, and the government will want to be careful in how it responds to the challenges to avoid the risk of fanning a fresh boom and bust cycle. In the short term, policymakers have released a series of measures to support economic growth and we expect more steps to follow. We believe those measures will eventually include significant fiscal stimulus to prevent excessive market stress.

In the short term, Chinese financial markets could remain quite volatile. But we think the long-term investment case for China remains intact, particularly in areas like AI, big data and other technologies.

Bumps in the transition to a domestic growth-driven economy

Overall, we view the property market problems as growing pains in China’s transition from a real estate and export powered economy to a model more focused on consumption and technology.

This shift began after the 2008 global financial crisis and has been fuelled largely by debt. As a result, China’s national debt level surged towards 300% of gross domestic product (GDP)1. Local governments and local government financing vehicles (LGFV) – designed to borrow money to fund property and infrastructure development – became heavily indebted and home prices multiplied.

But we believe the risk of a systemic crisis in the economy remains low in the short term. Measures such as extending debt maturities and bond refinancings have helped support local government finances. The Beijing government has also required developers to deleverage and taken a more cautious approach to approving infrastructure investments.

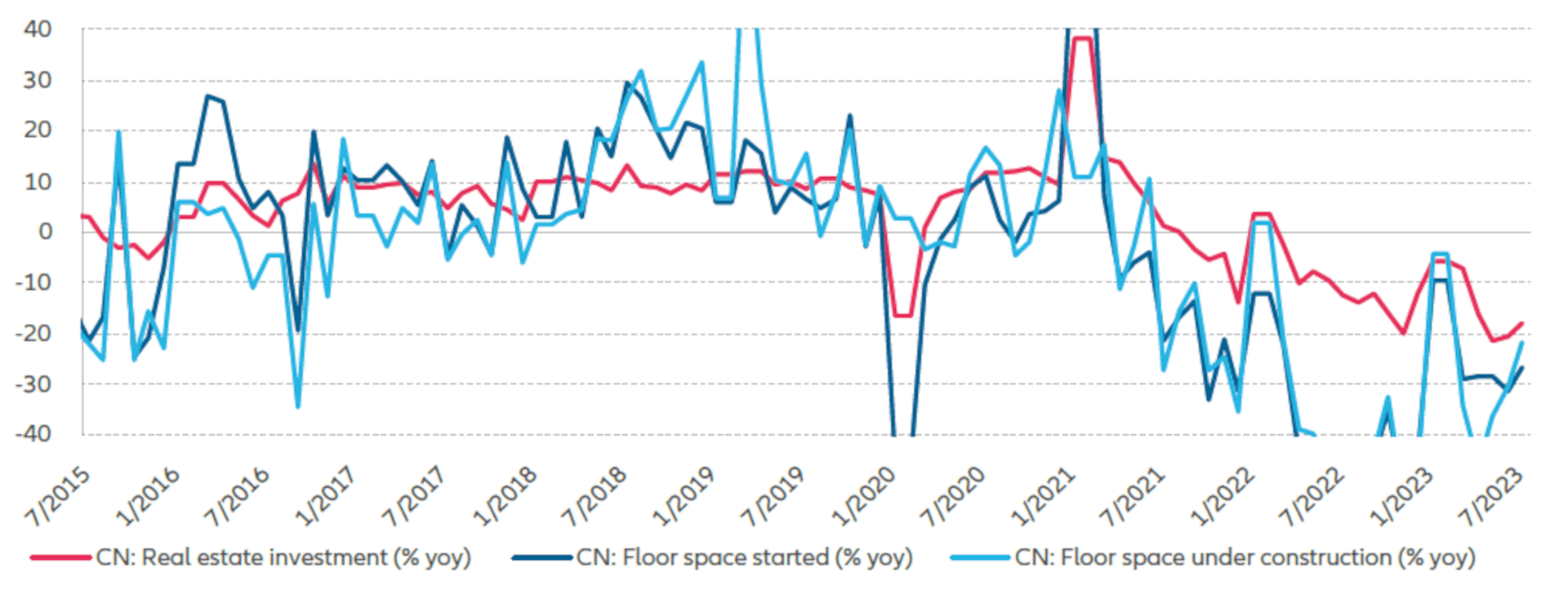

Activity in the property sector has been slowing (see Exhibit 1). Overall property development investment fell 8.5% in the first seven months of 2023 from the same period a year earlier, according to the country’s statistics bureau.

In our view, the government has so far been unwilling to unleash strong stimulus to support the property sector and wider economy, possibly to avoid the risk of moral hazard – the incentive for companies to take risks arising from insurance or governmental bailouts in the case of failure.

Exhibit 1: Activity in China’s property market has slowed dramatically

Sources: State Council, Wind, Barclays Research, AllianzGI Global Economics & Strategy. Data as at July 2023.

A decisive policy response is unlikely in the short term

With significant government intervention unlikely for the time being, we could see economic growth stabilise at a moderate rate, at least by China’s historical standards.

One reason for Beijing’s apparent reluctance to act may be its commitment to reducing the economy’s reliance on real estate. In other words, this kind of correction is a necessary part of the transition. The need to orient growth more towards domestic demand is made more urgent by growing geopolitical competition with the US.

Instead, Beijing has focused on fostering entrepreneurial spirit in the private sector through tax deductions and other measures such as giving private companies equal treatment to those run by the state.

So far, the private sector’s response has been muted and it seems that the government’s reluctance to conduct forceful stimulus measures has weakened business confidence in China’s cyclical growth outlook. Sentiment may improve as the government takes further steps to support the private sector, which will remain the key engine for overall growth.

But further stress may push the government to step in

The news is not all gloomy for the Chinese economy. For example, purchasing managers’ index figures showed manufacturing activity expanded for the third time in four months in August.2

But we doubt whether the measures so far announced by the government will be sufficient to turn the property sector around and revive economic growth. Despite the end of Covid measures, a lack of spending – as consumers hoard cash and companies are reluctant to invest – could lead to further deterioration in risk assets.

As cyclical growth momentum deteriorates and credit default risk mounts, we think there is a “pain threshold” at which point Beijing would unveil a more forceful stimulus to revive growth – even if it means raising national debt levels.

This stimulus might take the form of more support of the property sector and proactive infrastructure investments. Other measures to support growth may include measures to attract foreign investment, a pragmatic approach to geopolitics and an acceleration in policymaking.

As a result, the economic outlook may improve.

Focus on the long-term investment case

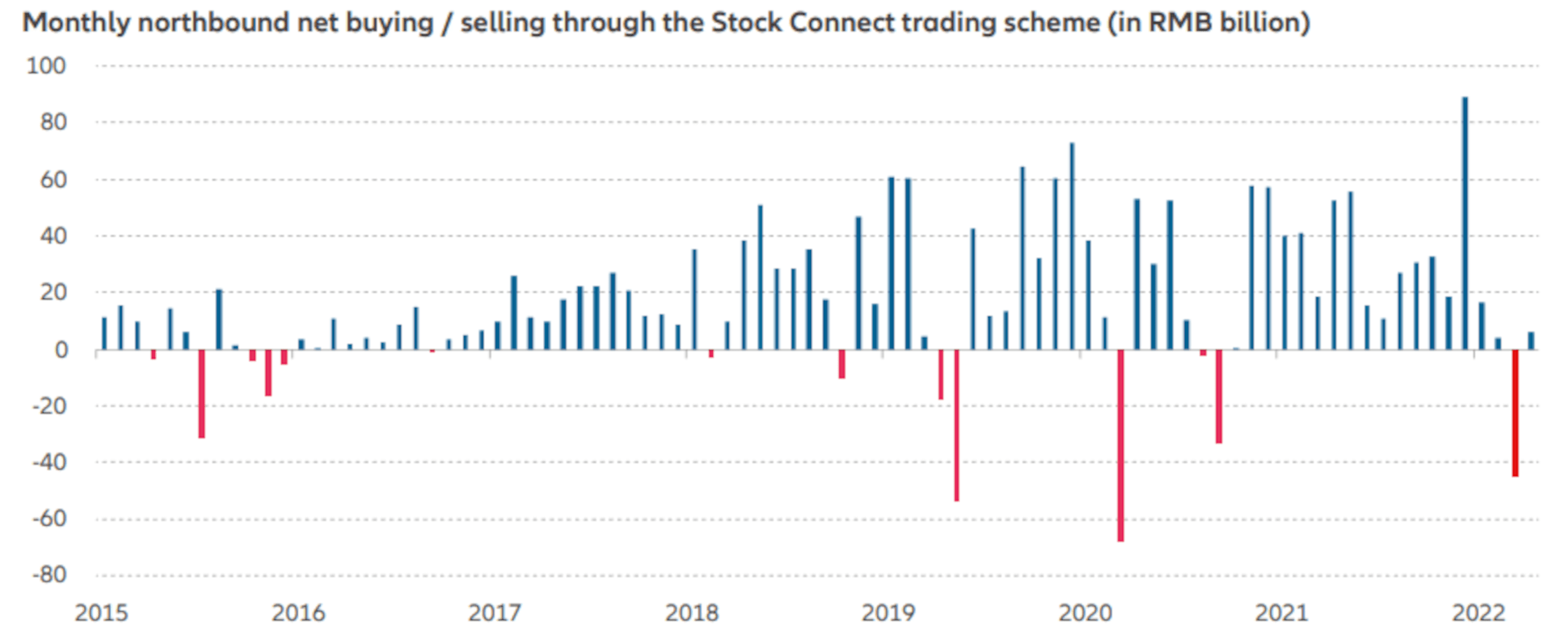

Markets have reacted with disappointment to economic developments and the government’s response so far (see Exhibit 2). Chinese equity, fixed income and foreign exchange metrics are trading at or near 2022 lows. But we think there are positives to consider across the main asset classes, especially at current valuations:

- Look to long-term trends in equities – Stocks rarely perform well when nominal GDP growth languishes below recent trends. With year-on-year growth currently around 5% – compared with a five-year moving average of about 7.5%3 – a sustained market rally may be unlikely. But given the pullback by some international investors from China equities and the recent market sell-off, there is potential for relatively fast and sharp rallies if positive news emerges (eg, about stimulus). In the current environment, stock selection will be critical. Certain sectors may perform well depending on where government policy is focused. For example, with the government action against technology companies seemingly over for now, the revenue of internet platforms may improve. The same may be true for sectors linked to AI and big data that are helping establish China as a key global player in these fields.

- Monitor opportunities in government bonds – China’s faltering economy has boosted demand for government bonds as some domestic investors consider alternatives to equities. This demand has helped push yields to their lowest levels since the Covid-19 pandemic. We think the yield on 10-year Chinese government bonds may go even lower than the current 2.5%4. But in the event of a stronger government response, bond yields may incrementally grind higher. In such a scenario, we would expect the yield on 10-year Chinese government bonds to range between 2.6% and 2.7% by the end of 2023. Expansionary fiscal policy directed at LGFVs may mean the vehicle’s bonds emerge as an attractive fixed income asset.

- Consider the renminbi’s long-term role – We expect the renminbi to remain under pressure. We think the People’s Bank of China will continue to support the currency —to manage volatility – but will mainly aim to avoid excessive moves which could trigger additional capital outflows. But if the pace of depreciation is well managed, it may be welcomed by policymakers given the potential boost to exports. In the longer term, the currency is set to gradually capture a growing market share in global payments. Policymakers are pushing to internationalise the currency, a process that will take many years.

Exhibit 2: Foreign investors have been exiting Chinese equity positions

Source: Wind, Allianz Global Investors, as of 31 August 2023.

Implications for the global economy?

The challenges facing China’s economy will likely have a broader impact. China has emerged as an important engine of the global economy and weaker performance in China may hamper global growth. China is also a significant driver of commodity markets. Any further deterioration in Chinese GDP data could lead to lower prices of industrial metals and energy. For example, prices of copper – viewed as an indicator for the health of both the Chinese and global economy – have already fallen this year5 on weaker Chinese and global demand. Still, copper prices may benefit from higher demand from “green” uses such as electric vehicles (EV) and renewable energy at a time of low inventory levels in China.

In the shorter term, China’s challenges may help cool global inflationary pressures to a limited extent. But we think inflation elsewhere in the world will still be slow to retreat. The current main driver of price pressures in the US and Europe is core inflation (stripping out volatile commodity prices), which may not moderate without a sustained economic slowdown. Even so, investors in the rest of the world will be closely watching how China resolves its property crisis for clues about how its economic transition may progress.

In the short term, the difficulties may undermine hopes for prosperity in the Year of the Rabbit, but investors should be mindful of another of the rabbit’s other symbol: longevity. And we believe the longer-term outlook for China remains strong.

1 Source: BIS Statistics Explorer: Table F1.1, Bank for International Settlements. Data as at Q4 2022.

2 Source: Caixin China General Manufacturing PMI Press Release, August 2023

3 Source: China's frail Q2 GDP growth raises urgency for more policy support, Reuters, 17 July 2023; GDP growth (annual %) - China | Data, World Bank. Data as at 2022.

4 Source: AMBMKRM-10Y | China 10 Year Government Bond Overview, MarketWatch. Data as at August 2023

5 Source: MarketWatch. Data as at 6 September 2023