The crisis on our plates: finding potential in failing food systems

Summary

The war in Ukraine has highlighted that the current way of producing and consuming food is unsustainable. As the rising global population places greater demands on our food system, there is an urgent need to build a resilient and inclusive food ecosystem, meeting both planetary and social needs. Opportunities exist for investors across the value chain of global food production and distribution to help mitigate these risks.

Key takeaways

|

Food is more than a simple source of nutrition – it supports human health, development and well-being. The challenge is that current food systems are failing on two fronts. They neither sustain the global population equitably nor maintain the natural regeneration of our ecosystem.

Millions of people are undernourished at a time when roughly one-third of food produced is lost or wasted.1 Adding to this, the UN currently anticipates a global food crisis due to the situation in Ukraine. This comes amidst the most rapid inflation hikes for 20 years in some countries – one example being trade prices for vegetable oil jumping by almost 30%.

Without a systemic transformation, we risk failing to meet the targets set by the Paris Agreement and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Not only is the sector a high emitter of greenhouse gases (GHGs), but there is also the social impact of needing to feed an estimated population of 10 billion by 2050, more equitably and with greater resilience. Investors can play a role in directing capital towards building a more sustainable food ecosystem and supporting the shift towards a more inclusive, equitable future.

![]()

Greater inclusivity as core to a resilient and sustainable food system

Enough food is produced globally to meet the needs of an expanding population, whose average daily caloric intake has increased by 34% since 19472 . Yet around 800 million people globally suffer from hunger and three billion cannot afford a healthy diet3. We are currently off course to achieve the UN’s 2030 Zero Hunger target which stems from the universal right to adequate food4. By 2030 840 million5 are expected to suffer from hunger. At the other end of the spectrum, an estimated two billion are overweight or obese and at high risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). The global imbalance is clear.

The challenge is not new but the Covid-19 pandemic, the invasion of Ukraine and increased frequency of extreme climate events have exposed the fragility of our food supply chain, and ultimately food insecurity. Ukraine is the source of millions of tonnes of maize and wheat that are key staples, especially in more vulnerable areas, such as South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, women and young people are also disproportionately lacking in access to healthy and affordable food. Empowering them is essential to create a more inclusive food system that benefits everyone.

Achieving a deep transformation of food systems involves the recognition that they play a central role in contributing towards most of the 17 SDGs. Through powerful levers for transformation, sustainable food systems provide the opportunity for progress in achieving the SDGs by connecting society, environment and the global economy.

Exhibit 1: the central role of food – touching upon each of the 17 SDGs

Source: Allianz Global Investors and UN Sustainable Development Goals

|

“Global food production threatens climate stability and ecosystem resilience. It constitutes the single largest driver of environmental degradation and transgression of planetary boundaries.” Source: Professor Dr Johan Rockström, EAT Lancet Commission, January 2019 |

![]()

Sustaining a food system within planetary limits

Scientists in 2009 named “planetary boundaries” as the limits within which humanity can safely operate, develop and thrive. We have overstepped six of these nine boundaries, yet far fewer than half of the world’s 8 billion people have access to a balanced diet. A critical question is how do we feed a further 2 billion people by 2050 without placing additional pressure on climate and planetary boundaries? The challenge is immense: the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations estimates that our food systems will have to produce 50% more food by 2050 but with fewer resources.

The existing food system is caught in a trap of trying to increase agricultural productivity, while damaging soil and incurring reduced crop yields. To reverse this, we must minimise harm from food production, while accelerating practices that actively restore habitat, protect diversity and lower emissions. This is the concept of regenerative agriculture.

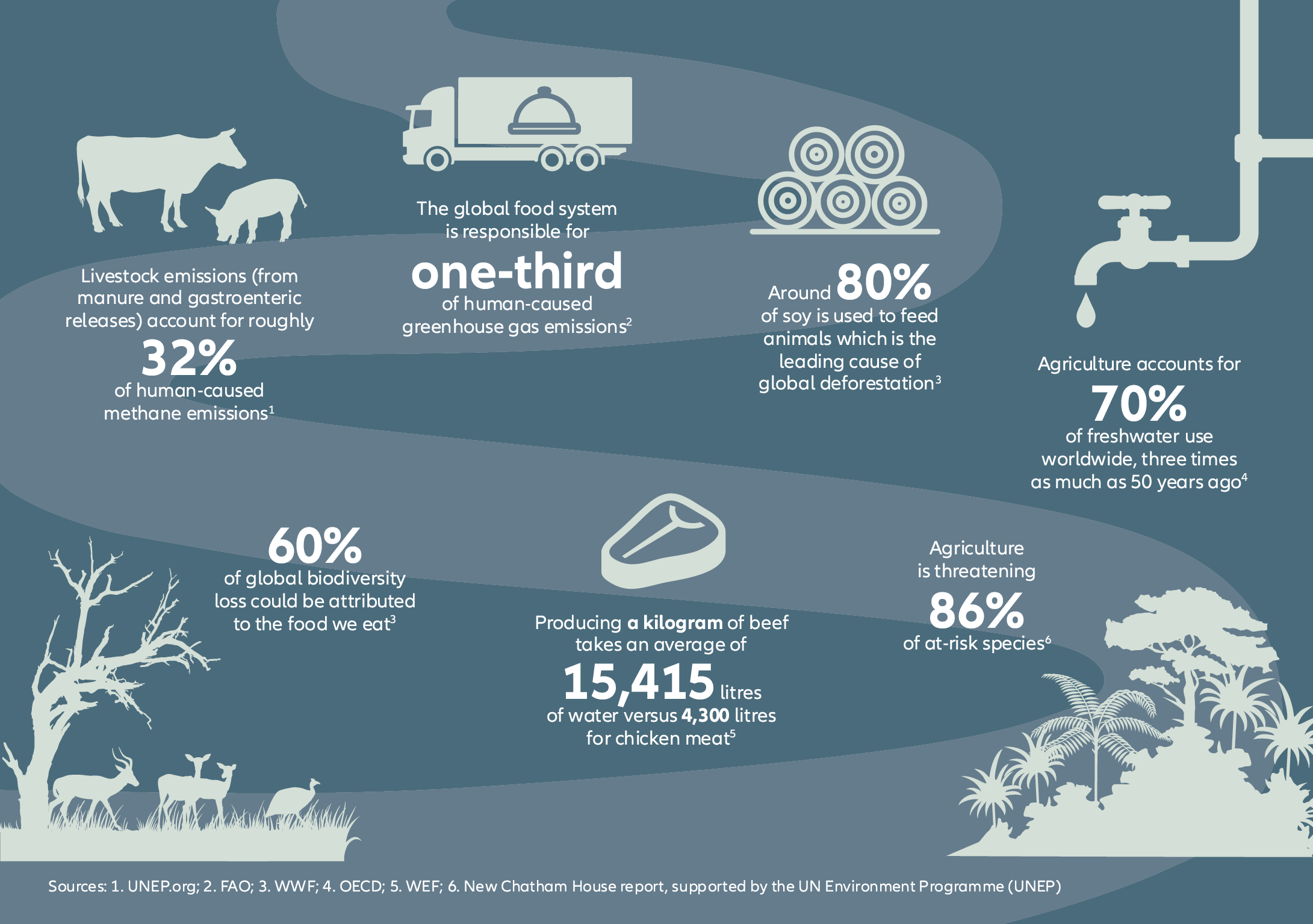

Exhibit 2: feeding the world is taking a toll on the planet

Sources: 1. UNEP.org; 2. FAO; 3. WWF; 4. OECD; 5. WEF; 6. New Chatham House report, supported by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP)

![]()

Global shifts in food consumption and diet

A key element to feeding the world’s rising population sustainably is what and how much we consume. This touches upon three key topics: food loss and waste, healthier consumption and alternatives to higher-emitting food products.

Globally, around 14% of food produced is lost between harvest and retail, and an estimated 17% of total global food production is wasted. Food loss and waste is estimated to contribute to 8-10% of total global GHG emissions. Furthermore, the estimated annual economic, environmental and social cost of food waste, according to the FAO, is USD 2.6 trillion. It is therefore legitimate to ask whether we need to significantly increase food production. Instead, how can we establish the even and equitable production and distribution of food, and direct any possible waste to those in need?

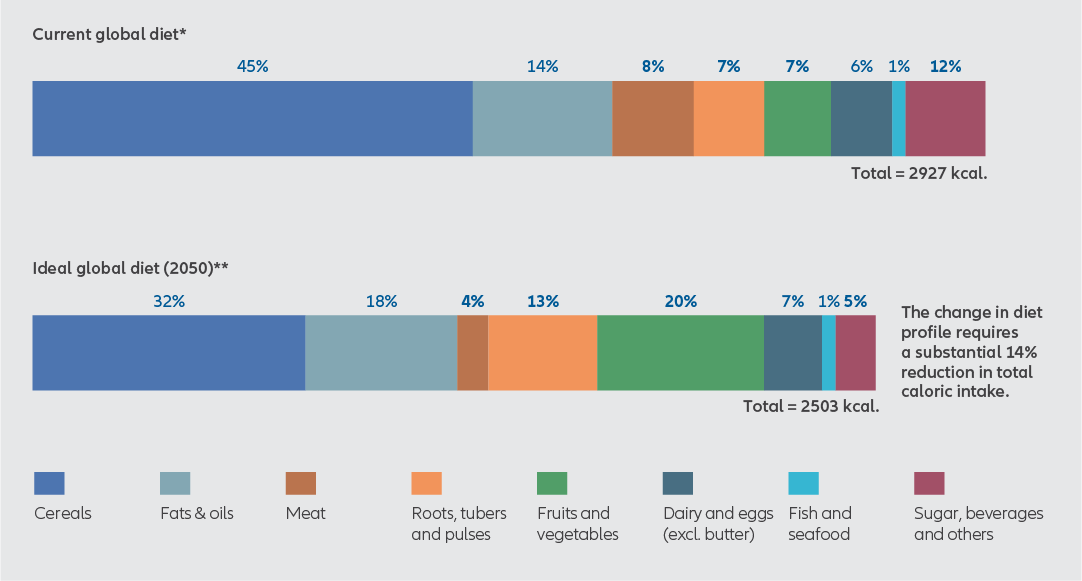

Lack of food for some people, and the consumption of excess calories for others, are twin pressures on global healthcare resources. In 2019, the EAT-Lancet Commission outlined a universal reference diet to “nurture human health and support environmental sustainability” and flag the risks of failing to adapt. A year later, the commission addressed the topic of affordability of this universal reference diet. The key finding comprises three areas of focus: transitioning to a predominantly plant-based diet, halving sugar consumption and halving meat consumption.

This last objective leads us to the need to consume protein differently. Global demand for protein is rising and is predominantly sourced from animal-based foods – meat, dairy and eggs. These are more energy-, land- and water-intensive and less calorie-efficient than plant-based proteins. For every 100 calories fed to animals, only 25 calories are produced in meat or dairy products. Lastly, overconsumption of meat is linked to rising levels of obesity and higher risk of NCDs, resulting in significant and rising financial costs to governments.

Exhibit 3: from current diets towards healthy and sustainable diets

Source: Allianz Global Investors, *Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (2018), **EAT-Lancet Commission planetary health diet (2019)

The planetary health diet does not prescribe an exact diet. The composition of a balanced and healthy diet varies according to individual needs, culural context, locally available foods, and eating habits.

Investing in food: three key opportunities

Investors can play a critical role in sustainable food transition and meeting global sustainability goals. The World Economic Forum estimates a USD 15.2 billion funding gap for food system innovation that would support ending hunger, keeping emissions within a 2°C rise and reducing water use by 10%. Innovation is essential for all 17 of the SDGs as well as the core priorities of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

There are opportunities to direct capital to a sustainable food ecosystem in line with different investment objectives:

1. Materiality of non-financial information

For investors seeking unconstrained universes, it will be important to identify evolving material ESG risks relating to the food ecosystem, including:

- Water intensity – rising scrutiny on water usage and management, especially for regions at high risk of drought

- Health regulation – public health and food safety are rising concerns for consumers and politicians alike. In addition, as obesity-related healthcare costs rise, companies could be at risk from new regulations, advertising restrictions, labelling requirements, product recalls and bans, and even higher taxation.

2. Screening – positive and negative

Evolving regulation is likely to drive a focus on the sustainable food transition within sustainable investment offerings. For example, under the forthcoming MiFID regulation, there will be reporting requirements on Principal Adverse Impacts. PAI 8 covers “emissions to water”, meaning pollution by emissions generated by investee companies. Additionally, many companies are under pressure to disclose data for water-management strategies and for water-use intensity.

3. Impact-focused investing

The triple challenge of providing safe, affordable and nutritious food for a growing population creates significant innovation opportunities. The potential to invest in “handprint” solutions are broad and expanding. While footprints are the environmental impacts of the processes that sustain us, handprints are positive changes – environmental and social impacts that we intentionally cause outside of our footprints. Below are some investment sub-themes attracting interest from investors:

- Precision farming solutions

- Circular economy – reducing waste through the redistribution of surplus edible food, recycling waste for animal feed and energy generation

- Flexitarian diets, and alternatives to meat protein and dairy

- Alternatives to existing commercial fishing

- Food-packaging solutions

- Affordable, nutritious and high-quality products

Additionally, food has direct and indirect reach into many of the SDGs. As a result, the sustainable food theme lends itself to impact-focused SDG investment strategies that are fully transparent and intentional.

Food for thought for investors

The current challenges around food availability and inflation could be a taster of more sustained threats in the long term, and they should urge us to reconsider our food ecosystems in a just and collaborative way. Economic policy, government policy and regulation must support this re-evaluation with a coordinated agenda of innovative policies. This intervention needs to be a high priority for several reasons, including: influencing consumer behaviour and buying decisions, improving food provenance and governance, impacting pricing to better reflect the true all-in cost of food options, motivating a just transition for the agricultural sector and the development of targeted financing programmes.

The transformative climate, health and geopolitical events seen in recent years have exposed the lack of resilience in the various value chains – with food production and distribution systems among the most notable – that are core to economic and social welfare. As we anticipate further unpredictable global events, now is the time to invest in a far more robust food ecosystem by contributing towards opportunities and innovations that embrace a sustainable, equitable and inclusive future for all.

Glossary of key terms

Food security – all people, at all times, need physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their food preferences and dietary needs for an active and healthy life (1996 World Food Summit). Food security encompasses four main dimensions:

- Food availability: the availability of sufficient quantities of food of appropriate quality, supplied through domestic production or imports

- Food access: access by individuals to adequate resources for acquiring appropriate foods for a nutritious diet.

- Food utilisation: adequate diet, clean water, sanitation and healthcare contributing to individuals reaching a state of nutritional well-being where all physiological needs are met

- Food stability: to be food secure, a population, household or individual must have access to adequate food at all times. They should not risk losing access to food as a consequence of sudden shocks (eg, an economic or climatic crisis) or cyclical events.

Food safety – the conditions and practices along the entire food supply chain that preserve food quality and prevent contamination and food-borne illnesses, with the assurance that the food will not cause harm to the consumer.

Food systems – all interactions and activities along the whole food value chain, from the production and processing to the distribution and consumption of food.

Healthy diets – a diet that provides enough of each essential nutrient, high in fruit, vegetables, legumes, nuts and grains, but lower in salt, free sugars and fats. Healthy diets help maintain or improve overall health (WHO).

Malnutrition – the condition resulting from getting inadequate or unbalanced nutrition and encompasses both under-nutrition (lack of enough nutrients) and over-nutrition (getting more nutrients than needed). Malnutrition results in poor health conditions.

Flexifood/flexi-diet/flexitarian – a plant-based diet allowing occasional meat dishes in order to reduce environmental impact and improve health.

Planetary boundaries – based on a scientific approach from the Stockholm Resilience Centre, the planetary boundaries concept, introduced in 2009, defines the environmental limits within which humanity can safely operate and continue to develop and thrive for generations to come. Nine planetary limits have been identified as regulating the stability and resilience of the Earth system: climate change, biosphere integrity, ocean acidification, ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosol pollution, freshwater use, biogeochemical flows of nitrogen and phosphorus, land-system change, and release of novel chemicals.

2030 Zero Hunger target – Zero Hunger is Goal 2 of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals. It seeks to eradicate hunger by improving access to food, ending all forms of malnutrition and developing agricultural productivity sustainably by 2030, through eight sub-targets and 14 indicators to measure progress.

1. UN Environment Programme

2. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) via Our World in Data

3. FAO 2021

4. The right to food is recognized in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights

5. Sustainable Development Goals – Goal 2: Zero Hunger

6. Source: Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, 2009

7. https://www.un.org/en/observances/end-food-waste-day

8. UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2021 https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021

9. https://www.thelancet.com/commissions/EAT

10. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(19)30447-4/fulltext

11. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/03/food-systems-innovation-transformation/

12. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

Investing involves risk. The value of an investment and the income from it will fluctuate and investors may not get back the principal invested. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. This is a marketing communication. It is for informational purposes only. This document does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security and shall not be deemed an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security.

The views and opinions expressed herein, which are subject to change without notice, are those of the issuer or its affiliated companies at the time of publication. Certain data used are derived from various sources believed to be reliable, but the accuracy or completeness of the data is not guaranteed and no liability is assumed for any direct or consequential losses arising from their use. The duplication, publication, extraction or transmission of the contents, irrespective of the form, is not permitted.

This material has not been reviewed by any regulatory authorities. In mainland China, it is for Qualified Domestic Institutional Investors scheme pursuant to applicable rules and regulations and is for information purpose only. This document does not constitute a public offer by virtue of Act Number 26.831 of the Argentine Republic and General Resolution No. 622/2013 of the NSC. This communication's sole purpose is to inform and does not under any circumstance constitute promotion or publicity of Allianz Global Investors products and/or services in Colombia or to Colombian residents pursuant to part 4 of Decree 2555 of 2010. This communication does not in any way aim to directly or indirectly initiate the purchase of a product or the provision of a service offered by Allianz Global Investors. Via reception of his document, each resident in Colombia acknowledges and accepts to have contacted Allianz Global Investors via their own initiative and that the communication under no circumstances does not arise from any promotional or marketing activities carried out by Allianz Global Investors. Colombian residents accept that accessing any type of social network page of Allianz Global Investors is done under their own responsibility and initiative and are aware that they may access specific information on the products and services of Allianz Global Investors. This communication is strictly private and confidential and may not be reproduced. This communication does not constitute a public offer of securities in Colombia pursuant to the public offer regulation set forth in Decree 2555 of 2010. This communication and the information provided herein should not be considered a solicitation or an offer by Allianz Global Investors or its affiliates to provide any financial products in Brazil, Panama, Peru, and Uruguay. In Australia, this material is presented by Allianz Global Investors Asia Pacific Limited (“AllianzGI AP”) and is intended for the use of investment consultants and other institutional/professional investors only, and is not directed to the public or individual retail investors. AllianzGI AP is not licensed to provide financial services to retail clients in Australia. AllianzGI AP is exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian Foreign Financial Service License under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) pursuant to ASIC Class Order (CO 03/1103) with respect to the provision of financial services to wholesale clients only. AllianzGI AP is licensed and regulated by Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission under Hong Kong laws, which differ from Australian laws.

This document is being distributed by the following Allianz Global Investors companies: Allianz Global Investors U.S. LLC, an investment adviser registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission; Allianz Global Investors Distributors LLC, distributor registered with FINRA, is affiliated with Allianz Global Investors U.S. LLC; Allianz Global Investors GmbH, an investment company in Germany, authorized by the German Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin); Allianz Global Investors (Schweiz) AG; in HK, by Allianz Global Investors Asia Pacific Ltd., licensed by the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission; in Singapore, by Allianz Global Investors Singapore Ltd., regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore [Company Registration No. 199907169Z]; in Japan, by Allianz Global Investors Japan Co., Ltd., registered in Japan as a Financial Instruments Business Operator [Registered No. The Director of Kanto Local Finance Bureau (Financial Instruments Business Operator), No. 424], Member of Japan Investment Advisers Association, the Investment Trust Association, Japan and Type II Financial Instruments Firms Association; in Taiwan, by Allianz Global Investors Taiwan Ltd., licensed by Financial Supervisory Commission in Taiwan; and in Indonesia, by PT. Allianz Global Investors Asset Management Indonesia licensed by Indonesia Financial Services Authority (OJK).

2200925

Summary

Recent examples of German supervisory boards adding the role of lead independent director (LID) are useful role models for their peers. A LID can help strengthen trust and improve communication between boards and investors. Additionally, it should foster independent, transparent and well-communicated succession planning, which can be lacking among German companies.

Key takeaways

|