Deforestation: getting to the root of the problem

The statement “there is no net zero without nature” has become a rallying cry for greater action against deforestation. The 2021 COP 26 pledge to end deforestation, and the 2022 COP 15 agreement on a Global Biodiversity Framework,1 have given greater focus to natural capital. Now, investors need to dig deeper, taking an active role to mitigate the risks of deforestation.

Key takeaways

- Covering 30% of the Earth’s landmass,2 forests are critical to sustaining world biodiversity and protecting local areas, while ensuring their economic viability.

- Deforestation and forest degradation reduce biodiversity and damage a vital element in the removal of carbon from the atmosphere.

- The monetary contribution of forests to the economies of the developing world has been estimated at USD 250 billion.3

- An average loss of 10 million hectares of forest per year in the last decade4 is prompting a greater recognition of biodiversity impact, resulting in greater inclusion into investment approaches.

- Investors can play a role by managing the risks related to deforestation and reducing the biodiversity footprint of investments.

Deforestation is defined as the conversion of forest to another land use. While the rate of deforestation has accelerated over thousands of years, the 20th century was a notable period when farmland and urban sprawl encroached on forests at a rapid pace to provide for booming populations.

Data shows the scale of this quickening pace of deforestation. Roughly 10,000 years ago there were approximately 6 billion hectares (ha) of forest, equal to 60,000,000 km2 . By 1900, this had reduced to 5 billion ha and by 2018 it had fallen to 4 billion ha.5 Forests are critical to sustaining global biodiversity, yet they are currently disappearing at a rate equivalent to 27 football fields per minute6 with 10 million ha lost in the last ten years.

Forest degradation is a related issue which plays a significant role in reducing biodiversity and preventing carbon removal. It is defined as a deterioration in the density or structure of vegetation cover or its species composition. This can be temporary or permanent.7 Degraded forests do have tree coverage, but their environmental contribution to biodiversity and carbon sinks is reduced. Fires, disease and pest infestation – in part caused by climate change – are among the factors responsible for such degradation, in addition to logging and agricultural activities. Between 2001–2015, it is estimated that around three-quarters of global forest loss was driven by degradation, while the remainder was from deforestation.8

DID YOU KNOW?

Afforestation is the conversion from other land uses into forest, or the increase of the canopy cover of a particular area of land by more than 10%. This includes the conversion of land to forest.9

Reforestation is the re-establishment of forested areas which have recently dropped below 10% tree coverage.10

Scale of the problem

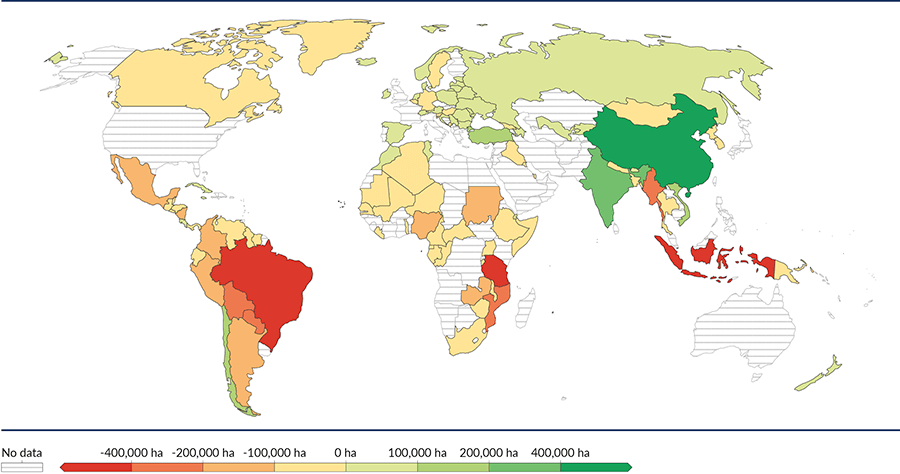

Forests cover almost one-third of the Earth’s land. Every continent excluding Antartica has been impacted by deforestation, but this problem has now become concentrated in specific regions. Half of the world’s forest coverage is in five countries – Russia, Brazil, Canada, the US and China – yet most deforestation is in tropical forests.

Exhibit 1: Annual net change in forest area, 2015*

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/deforestation11

* Net change in forest area measures forest expansion (either through afforestation or natural expansion) minus deforestation. Locations with a positive change, shown in green, are regrowing forest faster than they are losing it. Locations with a negative change, shown in red, are losing more forest than they can restore.

The good news is that the rate of deforestation seems to have slowed since peaking in the middle of the 1980s. However, action needs to be accelerated to avoid significant biodiversity risks and financial risks. For example, land erosion can contribute to the loss of biodiversity, while a reduction in crop production can expose companies in food production supply chains to financial risk.

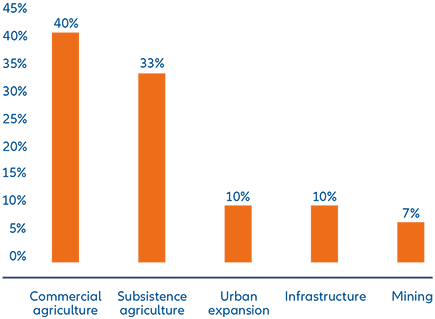

Agriculture – both commercial and subsistence – remains the greatest threat to forests as shown in Exhibit 2. Commercial agricultural activities include exports of cotton, soy and palm oil, while subsistence agriculture refers to meeting the needs of local communities. This data shows that despite efforts and improvements on several fronts, forests remain under threat.

Exhibit 2: Deforestation in tropical and subtropical forests by cause

Source: FAO, The State of the World Forest 2020

DID YOU KNOW?

Palm oil is one of the main drivers of global deforestation with 85% of this commodity produced in Malaysia and Indonesia, causing a significant and localised issue. Recent research suggested that deforestation due to palm oil had peaked in 2016 and then fallen below 2004 levels.12 However, this appears to have been driven by weak pricing. The rising inflation of 2022 has renewed interest in expanding the supply of palm oil. Pricing is now half of that year’s peak, but the focus is now to ensure any new plantations are both environmentally and socially sustainable. Evidence points towards a slow improvement in this situation.13

Five important roles of forests

The role of forests is critical and multi-faceted. This has implications for climate change, biodiversity issues, and the support of communities.

- Water management: the risks associated with the destruction of forests include higher land erosion, reduced soil fertility, and increased flooding. Land erosion can impact neighbouring waterways resulting in marine pollution, further pressuring local biodiversity and communities.

- Carbon absorption: healthy forests are natural carbon sinks – they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis which is then captured in the trees and forest soil. In contrast, degraded forests can be a source of carbon emissions. Protecting forests is critical as fires or even decaying wood will result in the release of stored carbon back into the atmosphere. Sustaining forests to allow for their role as net absorbers of carbon is vital for achieving decarbonisation targets and supporting the collective global goal of a clean energy transition.

- Ecosystem balance: forests are critical to maintaining the important balance and diversity of ecosystems. Around 60,000 tree species, 68% of mammal species, and 75% of bird species are living in the world’s forests.14 Disappearing forests are taking many species to the brink of extinction. The loss would be catastrophic on its own, but a decline in biodiversity can have material financial impacts. This is especially true for industry sectors like pharmaceuticals, materials, and chemicals where innovation is dependent on a diverse mix of animal and plant species.

- Social inclusion: many communities depend on forests for their livelihood, culture and way of life. Deforestation can risk a community’s income and health, posing a physical risk from the impact of extreme events such as flooding.

- Disease prevention: the removal of forests can lead to closer interactions between wild animals and humans. This could increase the risk of viruses and diseases spreading and the introduction of new epidemics.15

Deforestation as a political topic

Political momentum to end deforestation was evident at the COP 27 climate conference16 and later at its biodiversity equivalent COP 15, which included an agreement to protect at least 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030.17 Such high-level efforts are already having an impact on awareness of deforestation and are driving positive action. One example is opposition from several European Union (EU) member states to the free trade agreement with the Mercosur South American trade bloc,18 due to the impact on deforestation. A sustainability impact study for the EU Commission raised concerns that increased demand for soy and beef, resulting from this agreement, would cause a detrimental impact on the Amazon rainforest.19

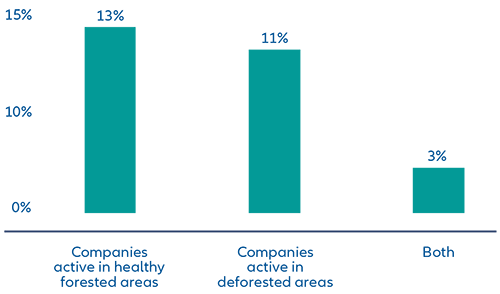

The EU is also in the process of adopting regulation which addresses deforestation in supply chains. This will require companies selling products in the common market to ensure that goods or their components/ingredients are not the result of deforestation. They will also need to consider their supply chain’s contribution to deforestation.20 This regulation is an important step forward for two reasons. First, it formally recognises the indirect impact that developed economies have on deforestation. Although these countries may no longer have deforestation in their own region, their demand for consumer imports can have significant negative impact. It is estimated that European consumption contributes to around 10% of global deforestation.21 Second, it directly connects all activities in the entire supply chain with their respective impacts on deforestation. Exhibit 3 shows that some companies are still directly exposed to deforestation through the location of some production sites. However, many firms may be exposed to deforestation through their supply chain activity.

Exhibit 3: Companies with production sites exposed to deforestation through geographical presence*

Source: Source: MSCI and Allianz Global Investors research as at 1 April 2023.

*Based on constituents of the MSCI ACWI.

What action can investors take against deforestation?

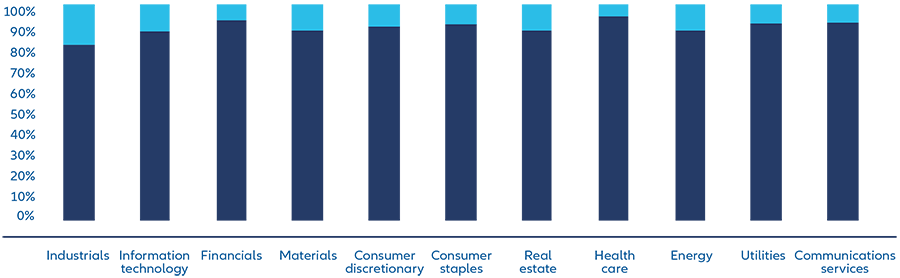

We expect deforestation to remain a high priority for investors in the coming years. It is a material risk for industries that rely on deforested areas for production. However, only a minority of companies are directly exposed in this way – see Exhibit 4. It’s likely that many businesses are exposed through their supply chains, although there is a lack of data to confirm this. Investors will want to identify those companies that are exposed to increased deforestation. EU legislation can support this, prompting fuller disclosures and a greater availability of data for investors, which is likely to further raise awareness and drive investor action.

Exhibit 4: Industry exposure to deforestation via company production sites in deforested areas*

Source: MSCI and Allianz Global Investors research as at 1 April 2023.

*Based on constituents of the MSCI ACWI.

We have identified three ways for investors to address deforestation in their investment approaches:

1. Identifying deforestation risk materiality

For investors, it will be important to identify companies that are exposed to deforestation – whether directly or indirectly – alongside how much risk exists in the sector they are operating within. Different approaches to identifying risks include:

- Screening for direct exposure through the location of production sites, as shown in Exhibit 3.

- Understanding the supply chains used by companies or sectors, as well as deforestation policies and practices. This is important as the products impacting deforestation are often further upstream in the supply chain.

- Engaging with companies is a critical tool in ensuring their awareness of the topic in the absence of appropriate disclosures. Engagement also enables identification of possible risks and the likely strategic initiatives required for companies to become resilient in this area.

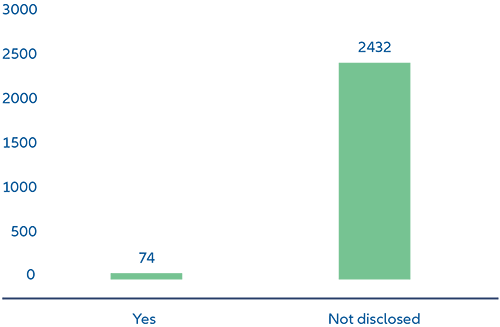

Exhibit 5: Number of companies with a deforestation policy*

Source: MSCI ACWI and Allianz Global Investors research as at 1 April 2023.

*Based on constituents of the MSCI ACWI.

2. Regulatory screening

The evolution of regulations including MiFID II22 led EU regulators to introduce formal Principal Adverse Impact (PAI)23 or Do No Significant Harm,24 screens in 2022. Three of the 14 PAIs on sustainability factors that are applicable to corporate issuers are aligned to biodiversity factors, with one specifically addressing biodiversity sensitive areas, including forests. These advances in regulation will provide additional pressure for improved corporate disclosures and we expect further evolution of the regulatory landscape to drive greater nature-based disclosures.

3. Impact investing

Investors can have a positive impact through the financing of sustainably managed forests and alternatives to wood as a raw material (providing that the alternatives to wood do not have detrimental impacts on sustainability). In addition, new financial products are being developed which may contribute towards reduced deforestation, for example:

- Carbon credits from sustainable forests. Refinement is needed on the scope, structure and governance of these instruments, alongside the long-term protection of these assets.25

- Forest bonds and other specific instruments.26 As above, consensus on principles and approaches will be needed to accelerate adoption.

Reforestation projects can also be financed. Many such projects are currently more philanthropic in nature. However, reforestation can help drive innovative financial solutions, to the extent that it is possible to put a financial value on the natural capital derived from forests.

Deforestation is a far-reaching challenge, both geographically and across our three pivotal sustainability themes: climate change, planetary boundaries (including biodiversity), and inclusive capitalism (including many social sustainability issues). The recent progress on globally coordinated policy alongside a regional focus is pushing deforestation into the mainstream for industry sectors and companies. This will not only prompt improved disclosures, but we anticipate it will also more formally embed this important sustainability issue into investment approaches.

1. UNEP, December 2022, COP 15 ends with landmark biodiversity agreement

2. BCG, June 2020, The Staggering Value of Forests - and How to Save Them

3. United Nations Forum on Forests, April 2013, Economic Contributions of Forests

4. FAO, 2020, The State of the World’s Forests

5. WEF, April 2022, Here’s How the Earth’s Forests Have Changed Since the Last Ice Age

6. International Forest Industries, January 2020, 27 football fields of forest lost every minute due to deforestation

7. FAO, March 2007, Manual on deforestation, degradation and fragmentation using remote sensing and GIS

8. Our World in Data, 2015, Deforestation and Forest Loss

9. WEF, April 2022, Here’s How the Earth’s Forests Have Changed Since the Last Ice Age

10. WEF, April 2022, Here’s How the Earth’s Forests Have Changed Since the Last Ice Age

11. Our World in Data, 2015, Deforestation and Forest Loss

12. CIFOR, 2021, Slowing deforestation in Indonesia follows declining oil palm expansion and lower oil prices

13. CIFOR, 2021, Slowing deforestation in Indonesia follows declining oil palm expansion and lower oil prices

14. UNEP, May 2020, Earth’s biodiversity depends on the world’s forests

15. IISD: SDG Knowledge Hub, July 2021, Preventing future pandemics starts with protecting our forests

16. COP 27 refers to the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference held in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt.

17. COP 15 refers to the 2022 United Nations Biodiversity Conference of the Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity held in Montreal, Canada.

18. European Commission, June 2019, EU and Mercosur reach agreement on trade

19. CIRCABC, August 2022, https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/09242a36-a438-40fd-a7af-fe32e36cbd0e/library/abfa1190-59d1-4f59-93a5-9b9810d2b744/details

20. European Commission, December 2022, Green Deal: EU agrees law to fight global deforestation and forest degradation driven by EU production and consumption

21. European Commission, April 2023, Parliament adopts new law to fight global deforestation

22. European Securities and Markets Authority, May 2014, MiFID II

23. Under the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulations, Principal Adverse Impacts are any impact of investment decisions or advice that results in a negative effect on sustainability factors.

24. Do No Significant Harm (DNSH) refers to products or services which do not harm any of the six environmental objectives in Article 9 of the EU Taxonomy.

25. FT.com, August 2021, US forest fires threaten carbon offsets as company-linked tress burn

26. International Finance Corporation, October 2016, Slide 1 (ifc.org) and Climate Bonds Initiative, Forest Bonds | Climate Bonds Initiative